Inside a West Village Townhouse Fit for a Culture Savant

Art-world maven Marlies Verhoeven’s family home beautifully marries serious works and whimsical accents

By Kathryn Romeyn

Photography by Gieves Anderson

August 7, 2019

a living room space with two chairs facing a sofa and a wall of windows

Most people lack the patience to search more than four years for the perfect home for their growing family. They’d eventually settle. But most people are not Marlies Verhoeven, who cofounded the global arts club the Cultivist. The Belgian-born CEO wanted a West Village townhouse—she and her husband, Jacco Reijtenbagh, couldn’t get used to apartment living—with a traditional exterior and modern interior that would gel with their contemporary art collection. “It wasn’t going to be something transitionary, it was something that would convey some of our values we grew up living in townhouses in Europe,” she says of their vision, adding that outdoor space was equally important.

First encountering this 1899 edifice, like every piece of art Verhoeven acquires for their robust collection—with its works by David Hockney, Mel Bochner, Jonas Wood, Mary Corse, Cecily Brown—left an indelible impression. As it happens, the home was one of the very first they saw; green to the market, they didn’t act fast enough, and it sold to other buyers. During the course of their ensuing search, they visited some 70 others. (“We can’t walk around the village on any street without having seen at least one or two houses,” she laughs.) But nothing compared. So Reijtenbagh found the buyer of their perfect place from years earlier, took him to coffee, and made a deal.

a tall living room space with a wall of glass and a modern hanging light fixture

A large “fiery” canvas by Korakrit Arunanondchai, Untitled (History Painting), replaced another piece Verhoeven lent to a museum for an exhibition, an example of the way the townhouse continues to shape-shift with time and new acquisitions. The mobile-like chandelier is by David Weeks; Verhoeven fell in love with it at his studio and bought it on the spot, before they’d moved in. “I love that lamp, it’s incredible,” she says.

Before moving in they removed all the lighting and made all switches and fixtures flush with the ceiling and walls—an obsession of Reijtenbagh’s. “It’s things you might not even notice, but they were very important to us so the focus could really go to the art and the furniture,” says Verhoeven. It’s gallery-like in the sense that the entire home was designed for a range of artwork to be shown and lived with at its best, not for a particular piece to shine.

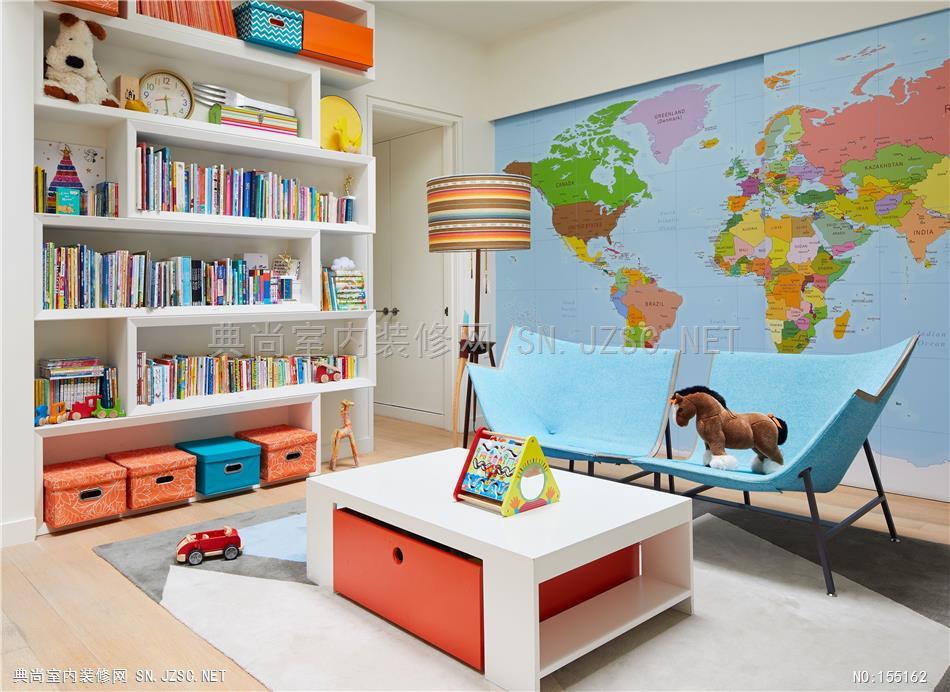

Important works from Verhoeven's studio visits for work mingle with fine furniture from America, Holland, and Europe, married in a way that’s not too precious but undeniably elegant. (Yet it’s outside, in their spacious backyard, with no art at all, that receives the bulk of the family’s attention and time.) Interior designer Kati Curtis helped distill Verhoeven’s thousands-of-pins-deep Pinterest board—“I had a very particular idea of what I wanted," the homeowner says—into a viable plan. Curtis hunted down specific additions and uncovered fun pieces her client hadn’t seen before, like those for the daughters’ playful bedrooms. The art guru’s vision: warm and livable, a little fun and different, and not too formal or cookie-cutter. “The art needed to take center stage, so you can’t work with crazy wallpapers,” says Verhoeven.

FEATURED VIDEO

Inside Aerin Lauder’s Family’s Home in Palm Beach

More Architectural Digest Videos

ADVERTISEMENT

It was in her kids’ vibrant rooms that Verhoeven had fun going “a bit eccentric.” But the formal dining and living room epitomize her careful, patient, planned approach, as well as her proclivity for juxtaposing serious artwork with slightly whimsical pieces. Dan Colen’s Hippity Flippity!—a particularly meaningful feather- and tar-coated canvas that she feels is about seeing the beauty in hardship—hangs above a couple of giant Johannes Albers ballpoint pens. “We wanted to lighten it up to not take ourselves too serious,” says Verhoeven. “That’s how we approached all of this—because, you know, life is not so serious and nor should it be.”